VERNAL

JANUARY 6 – FEBRUARY 18, 2023

CAROLINE MINCHEW

Vernal is a series of photographic works that renders the life cycle of an ephemeral pool as a shifting, mirrored form. Within these pools, matter is produced by the wearing of surfaces and energy rises from rot. Photographed in a regrown forest for over a year, this work considers how multiple stories of land, ecology, and memory can weave together into a larger parable, where parallels are drawn between the relationship of caddisfly to an ailing soldier. Vernal pools are a malleable subject that embody how reaching beneath the surface darkness and decay reveals a spectral network that is very much alive.

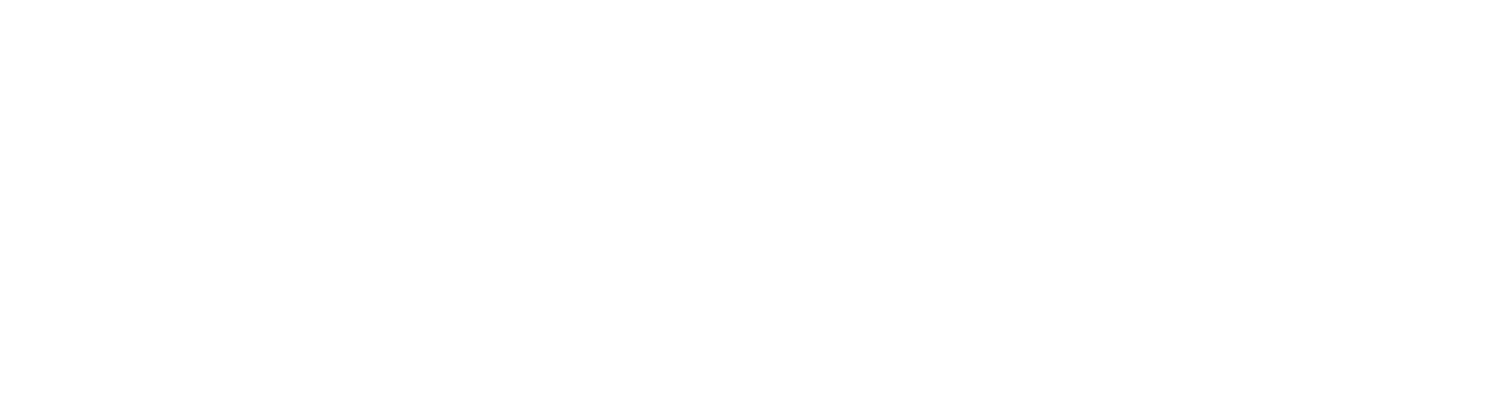

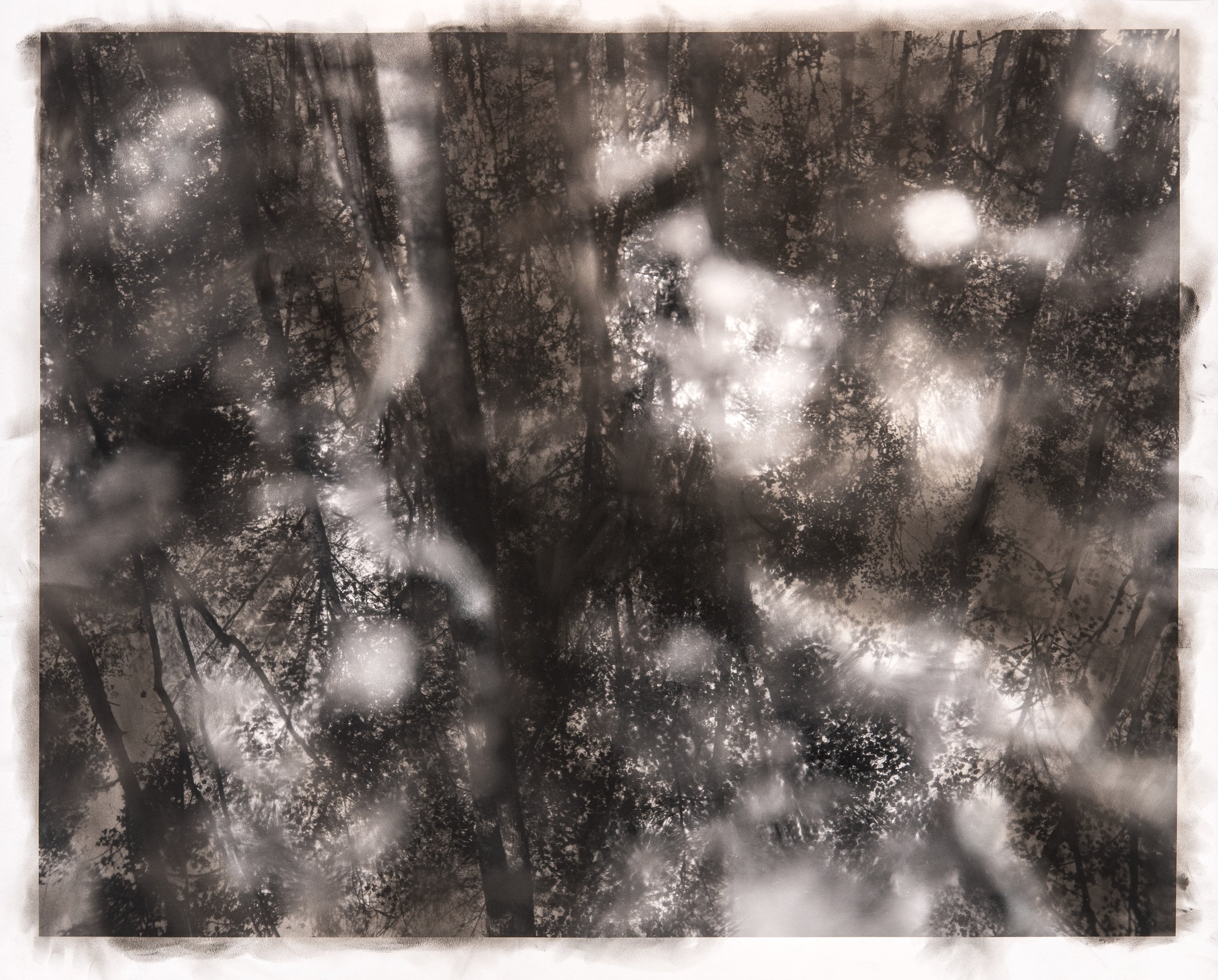

Mass, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 34 x 28 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

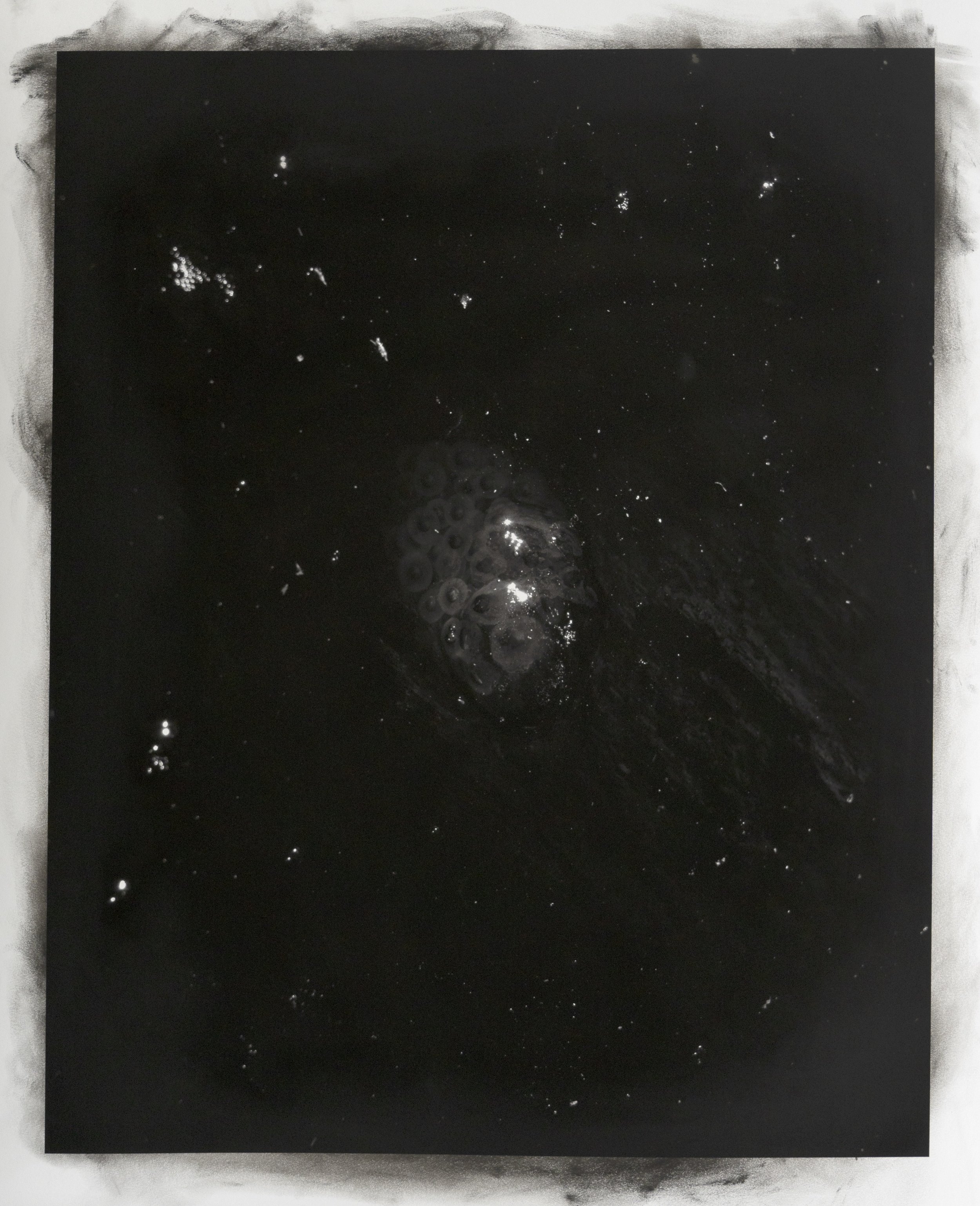

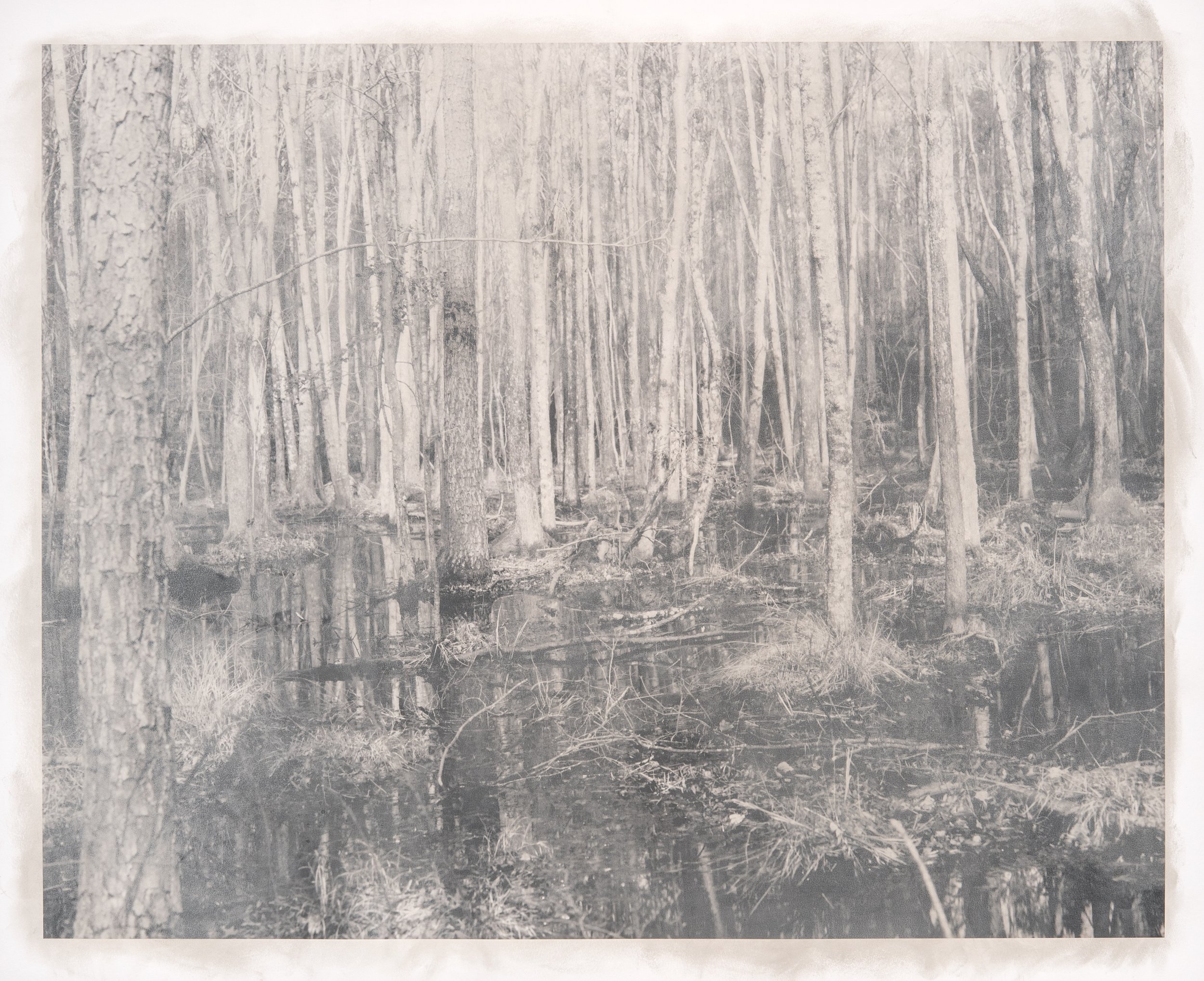

Vernal I, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 32 x 40 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

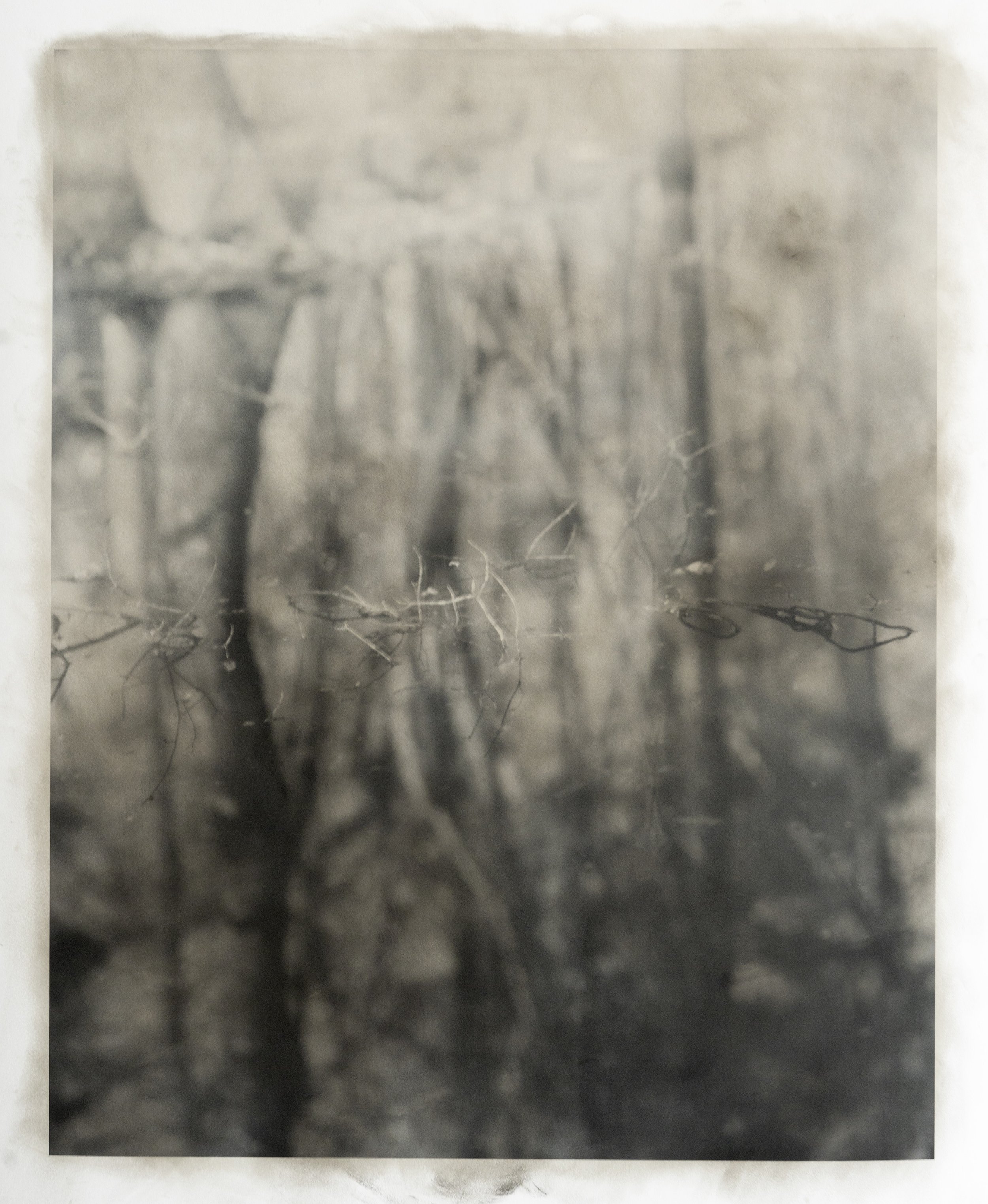

Vernal II, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 32 x 40 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

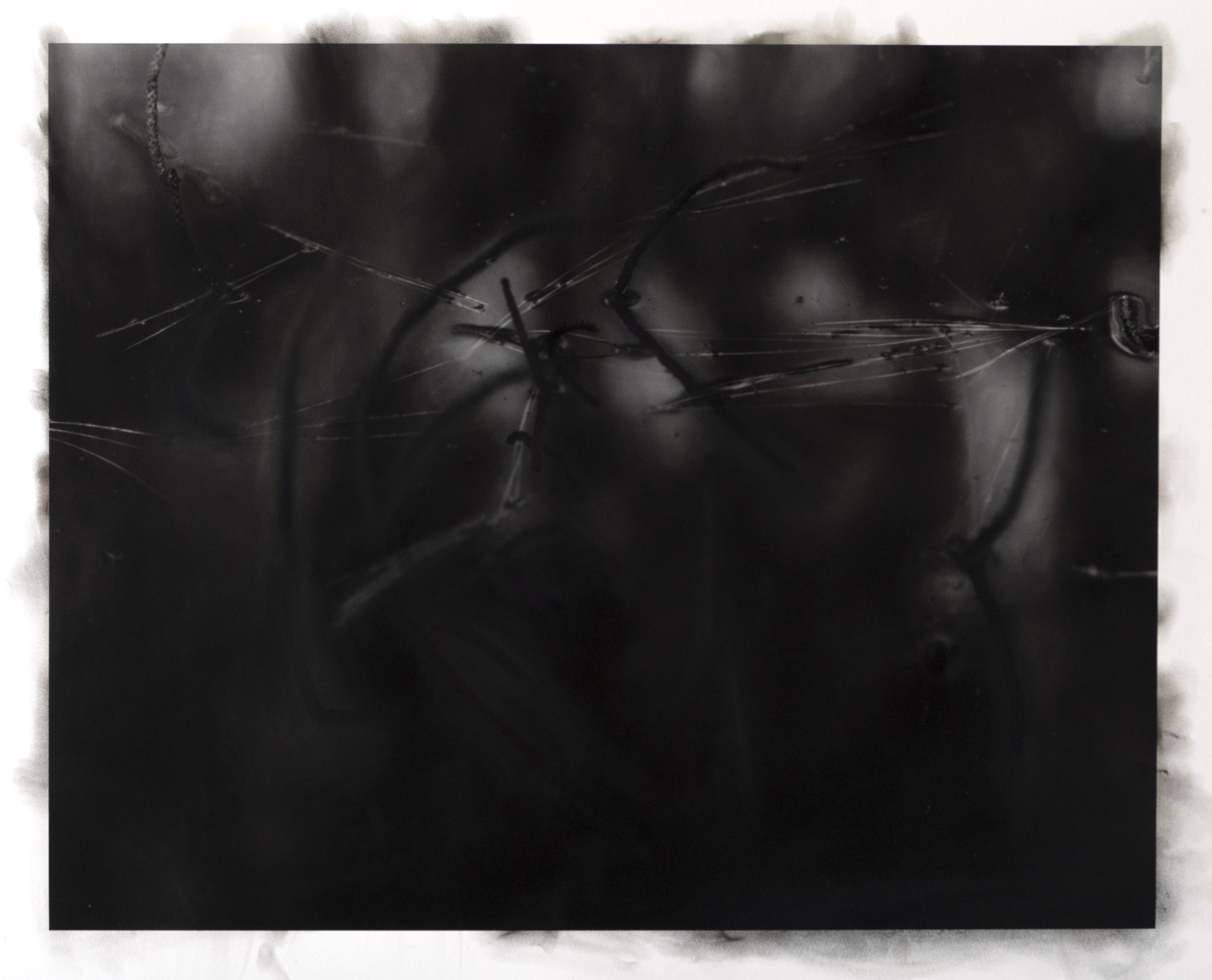

Vernal III, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 34 x 28 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

Vernal IV, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 34 x 28 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

Vernal V, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment, Indigo; 34 x 28 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3

Vernal VI, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 34 x 28 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

Vernal VII, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 34 x 28 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

Vernal VIII, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 34 x 28 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

Vernal IX, Archival Inkjet Print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, Charcoal, Natural Pigment; 34 x 28 inches, Framed. Variant Edition 1 of 3.

VERNAL

Vernal pools, also known as ephemeral pools, are depressional basins compacted onto forest floors. They have no inlets or outlets, and no visible connections to other mouths of water. Because of this, they are temporal sanctuaries that allow certain species, such as frogs, fairy shrimps, and salamanders to breed without the worry of a predatory fish. Many amphibious creatures such as the wood frog depend on vernal pools for breeding sites, many of which are bioindicator species.

The life cycle of a vernal pool has three phases and is as follows: wet, flowering, and dry. The wet phase occurs during the winter months, when rainwater and snowmelt fills the pools marking the beginning of many species’ life cycles. Next is spring, reproduction season, as eggs hatch, new life is made, and the pools slowly begin to dry out. Dry season completes the cycle. From summer to fall the water will completely evaporate, plants and aquatic life will die, but seeds, eggs, and cysts remain waiting to begin the cycle again the coming wet season. Three stages: birth, life, death, undulating waiting for one to tap in, one to sleep, and one to wait.

I’m interested in how one small site produces a multitude of stories and perspectives. Vernal pools became a point of interest to me through revisiting and embracing solitude at the site. Through conversations with a biologist the timely metaphors I was observing melded with the science I was learning. In essence, I kept returning to the site to uncover why I kept going back in the first place.

The physical materials used in the works connect the concepts of a vernal pool to the final form of the photographs in Wet, flowering, dry. The photographs are inkjet prints derived from scanned large format, black and white negatives printed on thick, matte paper. Their surface is covered, smudged, and drawn on with charcoal, bone black pigment, and slate pigment. In this process I mimic the detritus in vernal pools by actively layering materials that are steeped in compressed time and decay. Bone black is a pigment produced by carbonizing bones, creating a substance of bone ash and charcoal. The bone black pigment produces a heavy matte finish that I repetitively rub onto the surface of the print with my hands, effectively cloaking the inkjet print. The charcoal creates a shimmered effect, tracing the deep shadows with the negative and a subtle blending into the other pigments. Slate is powdered onto the highlights, illuminating alongside obscured darkness. As a collection, the prints balance between compositions where the pigments show a stronger hand in drawing, and those with unabstracted representation. I do this to act against representation itself,instead creating moments of illusion that create difficulty in deciphering between reflection and surface. The photographic element exemplifies aliveness, and eternal existence, while the drawing represents cessation through the demise of the surface.

The work is the result of many shifts in thinking of how I interact with the natural world as an artist, and the source of that interest. Prior to graduate school, my approach to landscape photography hinged on the idea of pristine and untouched nature, and the humanistic role to preserve that. I unknowingly amplified the age-old tradition in landscape photography of placing myself in the role of controller and capturer of landscape. I came to realize that a significant aspect of photographing in these natural spaces is being a part of every faction of energy, movement, and being that exists, seen and unseen.

The process of creating work in a singular site for over a year allotted time for me to reflect upon why I’m continually attracted to subject matter in natural and secluded spaces. The vernal pools represent a malleability to personify how we react to darkness and decay and being alive at the same time, free from a binary timeline. How do we avoid instinctively setting boundaries to a landscape? We simultaneously accept the scientific with the poetic. I like to think of the unseen and unfamiliar as a network of tissues that is understood, but not visible; like mycorrhizal networks that transfer energy underneath the dirt. By creating a clear geographic boundary to the site in which the work is made, directions in the work become meaningless. I am instead tasked with showing the connection in the macro and the micro, beings that inhabit the space, and the emotions that embody it.

The perspective of landscape in the artistic genre of Southern Gothic is a direct reflection of the falsehood of the pastoral vision of the South, instead revealing the reality of a culture embedded with slavery, racism, and patriarchy. The darkness in Southern Gothic works embrace a preoccupation with the grotesque, often exposing a tension between realism and the supernatural. In terms of the landscape of Virginia itself, it is difficult to extract the widespread death that occurred throughout the chronology of the colonization of Indigenous peoples, to slavery, into the Civil War, and the repercussions of these that exist today. Two-thirds of soldiers in the Civil War died solely because of disease due to poor hygiene and a lack of sanitation. The site of the vernal pools in particular records a public health disaster from June to July of 1862. 100,000 Union troops and 30,000 animals encamped deteriorated and suffered in a corridor of mud that recently was logged. You can see an obvious earthwork cutting through the forest, a humped road that confirms travel of humans, animals, and supplies to the encampment that summer.

Here, the past regularly returns, a constant process of rotting and decomposition, a burying and oxidizing of matter. There is an inherent lack of oxygen in swamps and wetlands that allows for high volumes of carbon storage, as soils are so saturated with water. Not only through the lens of ecology does a swamp act as a vacuum, again in the genre of Southern Gothic the swamp is seen as a site that is equally threatening as they are freeing, a place that chews and spits out, or a place of “wilderness linked liberation” for enslaved peoples. The swamp is a site of camouflage, its natural tendencies for overgrowth and darkness offer a blanket for which to hide in. While it is a refuge in which to disappear, it is also a sanctuary of terror, a humid environment difficult to survive in, riddled with poisonous creatures.

is the culmination of two years of quiet reflection and intention that resulted in a series of photographic works that speak to larger parables of life cycles. While the site in which the works were made is quite small, the representations of it transform the place to one that is otherworldly, ethereal, and ghostly. Time is bound to every essence of this work, from the photographic base to the bone black pigment’s source, and finally, to the physical time I spent there, absorbing and pursuing. It was a pleasure to submit to the seasons and create this work over the course of two seasonal cycles. To the best of my ability, I worked to remain unfettered by the pressures of quick artistic production. The trust in patient consideration allowed the final form of the work to reveal itself.